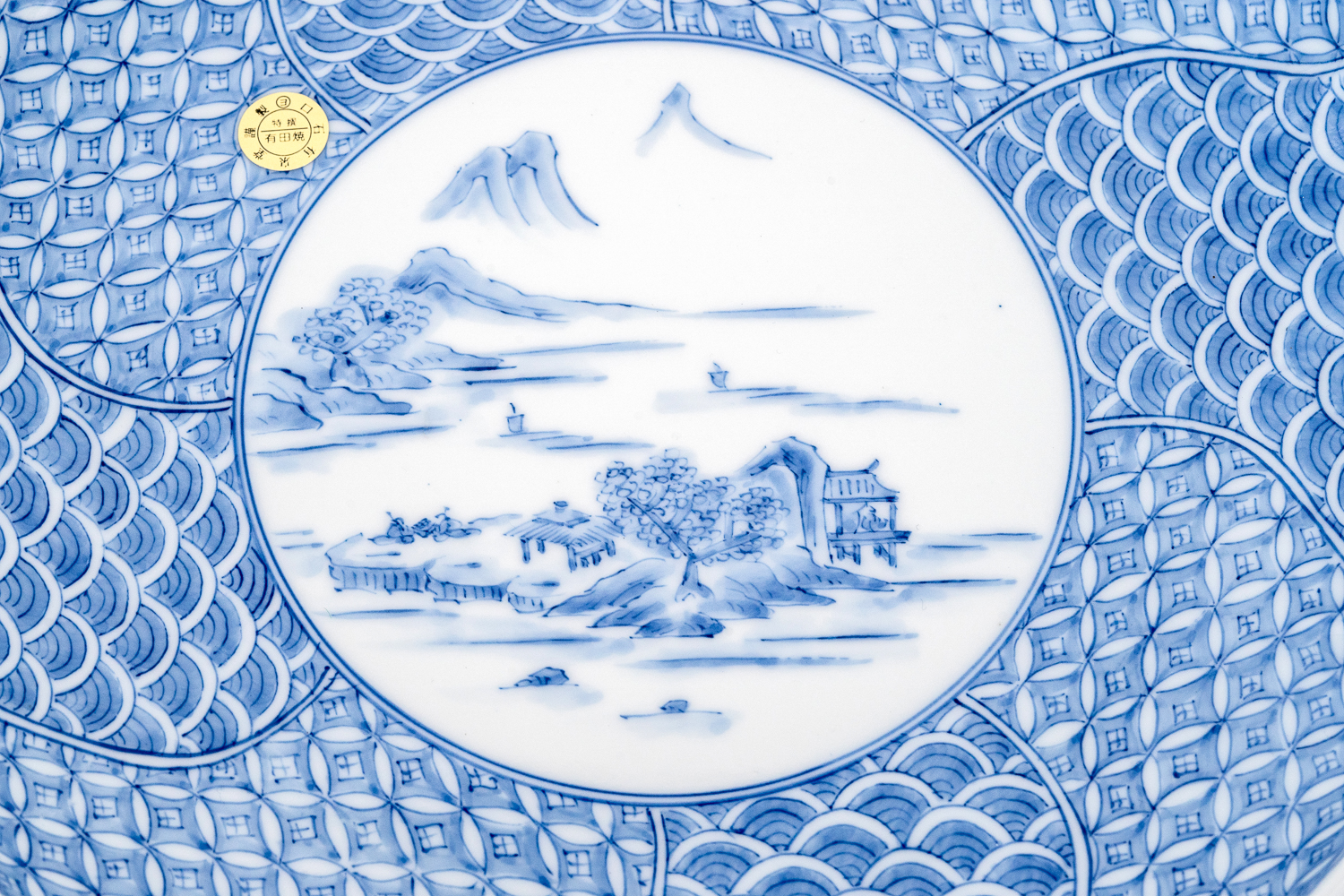

MIKAWACHI-YAKI

The Origins of Mikawachi Ceramics

The history of Mikawachi ceramics dates back to the late 16th century and is closely connected to the Korean invasions led by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (Imjin War, 1592–1597). After the campaign, the lord of the Hirado clan, Matsura Shigenobu, brought the Korean potter Koseki to Japan and established a kiln in Nakano (present-day Hirado, Nagasaki Prefecture) – a foundational point for what would become Mikawachi-yaki.

At the same time, potters from the Karatsu region (north of present-day Saga Prefecture) migrated into the area. Their techniques were also strongly influenced by Korean pottery. Due to political instability under the local ruler Hata, many Karatsu potters were relocated to other regions of Kyūshū, including Mikawachi (today part of Sasebo, specifically the districts of Kihara and Enaga).

From Earthenware to White Porcelain

Initially, Mikawachi produced rough earthenware, but around 1640 production shifted to white porcelain, sparked by the discovery of porcelain clay on Hario Island by Imamura Sannojō, Koseki’s son (1633). In 1637, Sannojō was appointed official master potter of the Hirado clan, and Mikawachi became a domain-sponsored kiln (kannayaki).

In 1650, the Hirado clan relocated all potters from Nakano to Mikawachi and established two main workshops — Eastern and Western kilns — with access to the finest raw materials and techniques.

From 1662, Sannojō’s son Imamura Yajibē (also known as Joen) began using clay from Amakusa, further advancing porcelain production. This period also saw the emergence of new decorative techniques such as openwork and relief designs.

Art over Commerce

Unlike private kilns, Mikawachi did not need to focus on profit thanks to the support of the Hirado clan, and could instead devote itself to achieving the highest technical precision. Until around 1789–1800, Mikawachi ceramics were produced exclusively as gifts for the aristocracy – commercial sales were prohibited, and the techniques were kept strictly secret.

The scholar Hiraga Gennai wrote in 1771 in his work Tōki Kufūsho (“Guide to Ceramic Art”) that if Mikawachi ware had been permitted for trade, it likely would have been as popular as Imari or Karatsu ware, especially among Chinese and Dutch buyers.

.

Sasebo, Nagasaki

1. Overview & History

Sasebo is the second-largest city in Nagasaki Prefecture, with around 230,000 residents. Since the late 19th century, it developed into an important naval base and today hosts both Japanese and U.S. naval forces. Its seaside location, deep natural harbors, and partially Christian architecture give the city a unique character.

Popular attraction: Huis Ten Bosch, a large theme and cultural park ensemble styled after the Netherlands.

2. Ceramics: Mikawachi-yaki (三川内焼)

Tradition: The porcelain tradition goes back over 400 years. Mikawachi-yaki was once produced as “elite tableware” for the aristocracy.

Technique & Style: Known for its ultra-thin, white porcelain with fine openwork and relief patterns. Decorations such as “Karako-e” (children in Tang-style) and “Rankaku-de” (eggshell pattern) are considered technical masterpieces.

Workshops: Around 14 traditional pottery workshops in the Mikawachi area continue to preserve the tradition of handmade ceramics.

3. Sasebo Spinning Tops (Sasebo Koma / Koma Goma)

Status: A local craft recognized by Nagasaki Prefecture as traditional handicraft.

Materials & Production: Made from hard native wood—traditionally the Matebashii tree—and lovingly painted in five symbolic colors representing the Chinese Five Elements philosophy.

Culture: Often used in competitive spinning matches (“Kenka Koma”). There are workshops where visitors can paint their own creations and learn the art of spinning them skillfully.

4. Artisanal Diversity & Cultural Network

Regional Pottery Traditions: The area around Sasebo also includes other renowned porcelain centers such as Hasami-yaki and Imari-yaki.

Cultural Heritage: Traditional villages and the ruins of the “Kannenweg” pottery route (including railway remnants and brick structures) add a vivid dimension to the town’s handicraft history.

Conclusion

Sasebo is much more than a naval hub – it is a vibrant center of Japanese craftsmanship:

-

Mikawachi porcelain: A symbol of the highest technical precision and aesthetic refinement.

-

Spinning tops (Koma): A fascinating example of traditional wooden toys that unite art, philosophy, and daily life.

-

Regional density of crafts: Sasebo is nestled in a network of Japanese ceramic culture, enriched by museums and hands-on workshops.

A city where history, art, and regional identity are alive and tangible – ideal for visitors interested in authentic Japanese craftsmanship and cultural heritage.